This time, dear readers, it is about me. For once.

We have discussed moral philosophy. It really is all a little grim when one thinks about it. We have delved a little into metaphysics. But what can be said about such stuff? Meaningless- most of it. What's next?

Once Hume had decided that there were only two types of truth, necessary and contingent, and that there were some serious problems with the notion of 'causality' he cast a spell so deep upon the foundations of philosophy itself, that there really has never been a full recovery from this event. And a good thing too. Best philosophy hobbles along in the right direction than elegantly runs towards and leaps from the edge of a cliff to its eventual death. (Actually, I think I prefer the elegant leap- so this was not at all a good illustration.)

Hume suggested that we never have observational evidence to support any judgement that one event has caused another to happen. In other words, the only thing that pure unadulterated observation can give us, is that one event happened and that immediately afterwards another happened. But, according to Hume, this is not evidence for a causal relationship. Why?

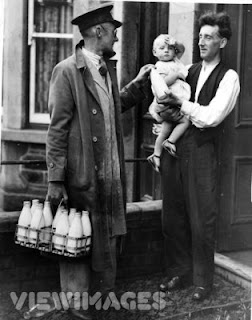

Maybe a story here: If, every morning when I wake up, the milk man comes to my door at 7:15 and delivers milk to me and then at exactly 7:16 the newspaper man comes and delivers my news paper, most of us will agree that the only information we really have is that the one event always succeeds the other, in a particular order and without fail (if this is indeed the case). Not many of us will want to add to this that that the milkman has caused the newspaper man to arrive. Most of us accept that these two events have two external causes of their own, entirely seperate from each other.

Now, this seems intuitively true because we happen to know something about how these systems work. But what if we are looking through a microscope and see two organisms, both unknown to us, repeatedly performing some sort of action wherein the one turns red and then the other turns blue immediately afterwards when they come into contact with each other. Every time. We have observational evidence of the proximity, we have observational evidence of the change of colours. We have no evidence that the one causes the other to happen.

For Hume it is necessary to show a logical connection between two events, in other words, when this event happens that one must follow, and it must be for that reason only (the first must be a necessary and sufficient condition for the next event to happen) before any causal links can be assumed. A high bar to set for causality. And such a wet blanket, because we do so love to think that we know what caused what to happen.

OK. This is enough for today. One lesson at a time. This will need to happen in incremental steps, for my sake.

Next lesson: Two types of truth and what this leaves us with.

4 comments:

This is brilliant. Certainly clearer than Sophies World (do you know the book?). Your illustration of the pitfalls of casuality was crystal.

A couple of questions form your admiring dummy -

What is meant by a necessary or contingent truth?

How do you establish if event A is a necessary and sufficient condition for event B to take place.

what if event A can have outcome event B or event C (or maybe more than two possible outcomes), does this mean cause and effect are not established? And the corollary if event C can be caused by either event A or B, does that also mean there is no cause and effect?

P.S. in this subjective world is it not always about you?

Yes yes yes! Thank you. Hume has taken a grasp of your imagination and excellent sense of logic. I suspect my work is nearly done.

'Necessary' and 'contingent' will be lesson two, so please wait for another, hopefully, crystal clear explanation.

And you are exactly right: If event A could have outcomes B or C then a necessary and sufficient condition has not been established between any of them. And the corollary is true also, if event C can be caused by either A or B then no necessary cause has been established.

When we, next, talk about 'necessary' and 'contingent' it should become clearer why necessary causes are the only causes that count and why these are, in the end, impossible.

Which is why Hume was a sceptic about knowledge, and then so on to positivism and then to anti-realism.

It's a journey.

Thank you for your comment.

Oh, and I did once try to read Sophie's World. But could not get even a few pages into it. Did not like the style. But maybe I should try again?

Don't bother with Sophie's World. It was written for the likes of me, not you. You would find it simplistic.

I am interested in your ever changing profile.

Tell me about the 'Chemicals' industry that you are involved in and your audio visual (empty) blog.

Just one more question about Hume's scepticism towards knowledge. Presumably this means that Bacon and the hugely succesful induction technique is rubbished. If so then gravity does not exist. This rather flies in the face of common or any sense and the huge technological success of the last few centuries.

Looking forward to the next episode; so much better than Isidingo (never watched it actually!)

Thank you for your blog and sharing your knowledge (and wisdom)

Post a Comment